Carrara's Marble - Part 1

Context | The Summer of 2016, I began working with Kristina Grace, sculptor Robert Gove’s artist representative, to study and document his work. I was captivated by what I learned talking with Kristina and Robert, as well what my own research began to uncover.

At first, I kept trying to wedge way too many stories into a project case study. Finally, I decided to find a more appropriate place for my enthusiasm. My collection of quotes, images and omg moments found a home here, with Carrara’s marble and the mountains it came from.

The town of Carrara sits below the marble-rich Apuan Alps.

It isn’t snow on those peaks. It’s not a stretch to say that the Apuan Alps are made of marble, all the way up to the tippy top. Having been quarried for 2,000 years, the tippy top isn’t quite what it used to be. But still...

“There’s enougn marble in these mountains to last an eternity,” a quarryman remarked ... “Enough to build an Autostrada (highway) to the moon.”

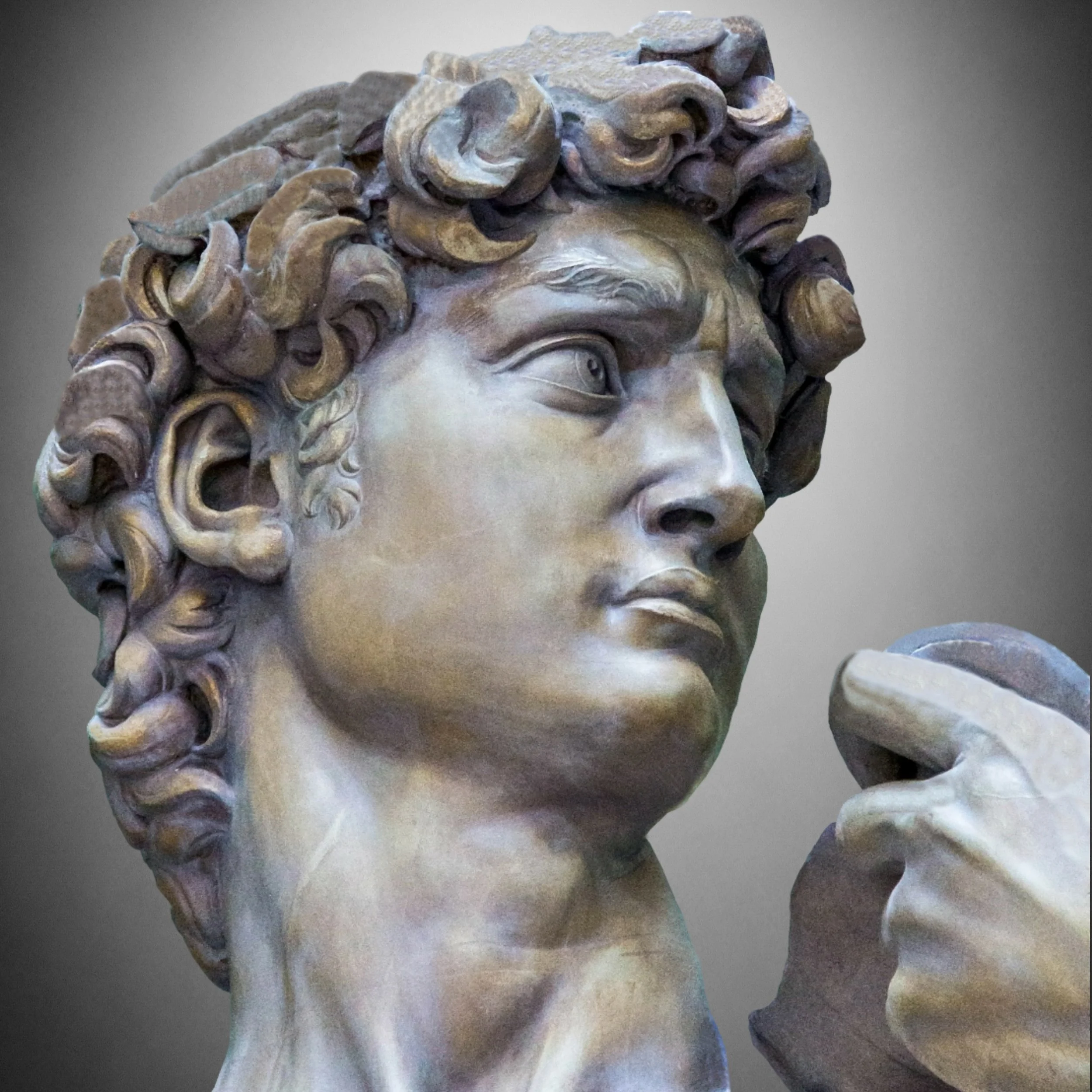

Prized since the Romans, they say there’s is no stone like this Carraran marble. Fine-grained and luminous, with a translucent and emotive quality, it's also famous for being easy to work with. Artists as renowned as Michaelangelo and Bernini carved Carrara marble for its capacity to be worked to refined plasticity. In fact, most of Michelangelo’s marble statues were carved from it. He personally chose blocks and oversaw their extraction and transport.

Michelangelo’s David

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne

This stone, with the grip its special qualities has on artistic and commercial imagination, has engendered Carrara's 2,000-year-old tradition of quarrying and carving, in a symbiotic relationship with danger and destruction, business and art, technology and education.

And where there are people, there are stories and culture. The Massa-Carrara area’s culture and language has been shaped by working the marble.

Ars Technica: The How of It

For centuries, small armies of people have worked to slice out huge blocks of marble and slide them down the mountains on zig-zag paths. It is hard, dangerous work that demands a focused awareness of practical physics in real-time. A lapse could cost a life.

The Romans built the port of Luni in 177 BC to prepare and ship Carraran marble. Mining really picked up during the the reigns of the Caesars, from Julius through Augustus. You can see signs of this early mining today. And if you visit Rome, any marble from that era came from Carrara.

Serious excavation efforts were abandoned at the fall of the Roman Empire. But, during the Renaissance, Carraran mining sprang back to life with the boom of explosives. Very “efficient”— this then-new technology dislodged a lot of usable stone while drastically reshaping the mountains.

It pulverized plenty and created (literally) tons of loose rubble that litters the mountains, ledges, and streams. The rubble also adds to the dangers of working the mountains and blocks access to other mineable marble.

La Lizza

During the Renaissance and until the 1960s, la lizzatura was still used to get the huge blocks of stone off the mountain. Though ingenious, the system is also a corporate safety officer’s white-knuckled nightmare. It evolved from Greco-Roman strategies for moving big things a long way.

On the mountain, workers would lever a block of marble onto a couple of roughly shaped wood skids and then slide the semi-precarious stack of stone down and around hairpin switchbacks.

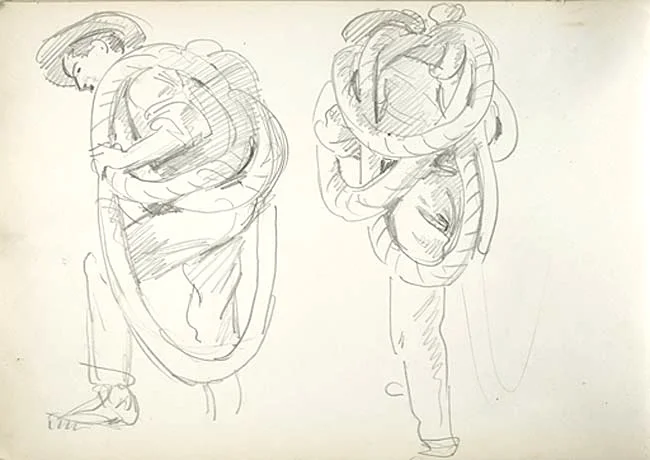

Bringing Down Marble from the Quarries to Carrara, oil on canvas, John Singer Sargent, 1911

If anyone can really be said to control shed-sized rock tonnage sliding down an alpine slope, these teams managed it with ropes, soap, wooden cross pieces, and fancy footwork. They would control the skid by twisting those ropes around wooden posts hammered into the stony slope. It was a highly choreographed and very dangerous dance.

John Singer Sargent’s studies quarry workers on the slopes of the Apuan Alps

Eric Scigliano says that the Massese used 3 ropes for their lizza, but the Carrarese only used 2. I can only sputter at the thought.

“In the old days, ...this (dangerous) work precipitated the evolution of... daredevil specialists... The danger and the (pride in)... these jobs shaped a culture that still sets Carrara apart from the rest of the world—and, it often seems, from ordinary reality.”

The Quarries Today

La lizza was the last ancient practice to fall under modern industrial improvements. They started using steel cable in the 1890s, then progressed to the diamond-studded wire saws in use today. Now, the mountains have roads and heavy lifting equipment, so the only way you’ll witness the lizzatura is during the annual re-enactment in August. You can buy tickets and take the family.

Some former workers conduct hiking tours, where you can exert yourself by scrambling up and around the mountain, without having to haul marble.

Annual Re-enactment | With a ticket, you can watch while volunteer lizzatori get a good-sized chunk of marble down the mountain and then across the 10 kilometers to the sea. Volunteers are rewarded with colazione del cavatore: a lardo and tomato panino with rosé.

Watch Apuan quarrying in action

The video is in Italian, but you’ll get the idea of what “reshaping the mountains” with explosives was like. An example of this starts at 3:40. The lizzatura starts at 4:48, with the sledge ready to move at 5:30.

Footage from an Italian documentary shows the quarry in action.